On being ill – A Corona diary

The pandemic we have lived through has affected my work, also because I chose to include it in it. My research evolves around Virginia Woolf’s life and work as a self-publishing author and letterpress printer, a little known fact.Virginia Woolf, like so many times before, gave me tools to understand this situation we’ve found ourselves in. 2020 was all planned out. I was to start a project about Kew Gardens (which I’m working on right now) but Covid-19 put and end to all our plans and they were replaced by fear and confusion.

A couple of days into Lock-down I read the essay On Being III, Woolf’s third and last work she typeset, printed and published in 1930. The essay was written int he wake of the Spanish Flu, and in it Woolf reflects around illness; loneliness, isolation and vulnerability. In addition, the essay speaks to how, when we are forced to stay still we’re more capable of discovery and of appreciating the small details in the world around us, and that it is our daily life we miss most.

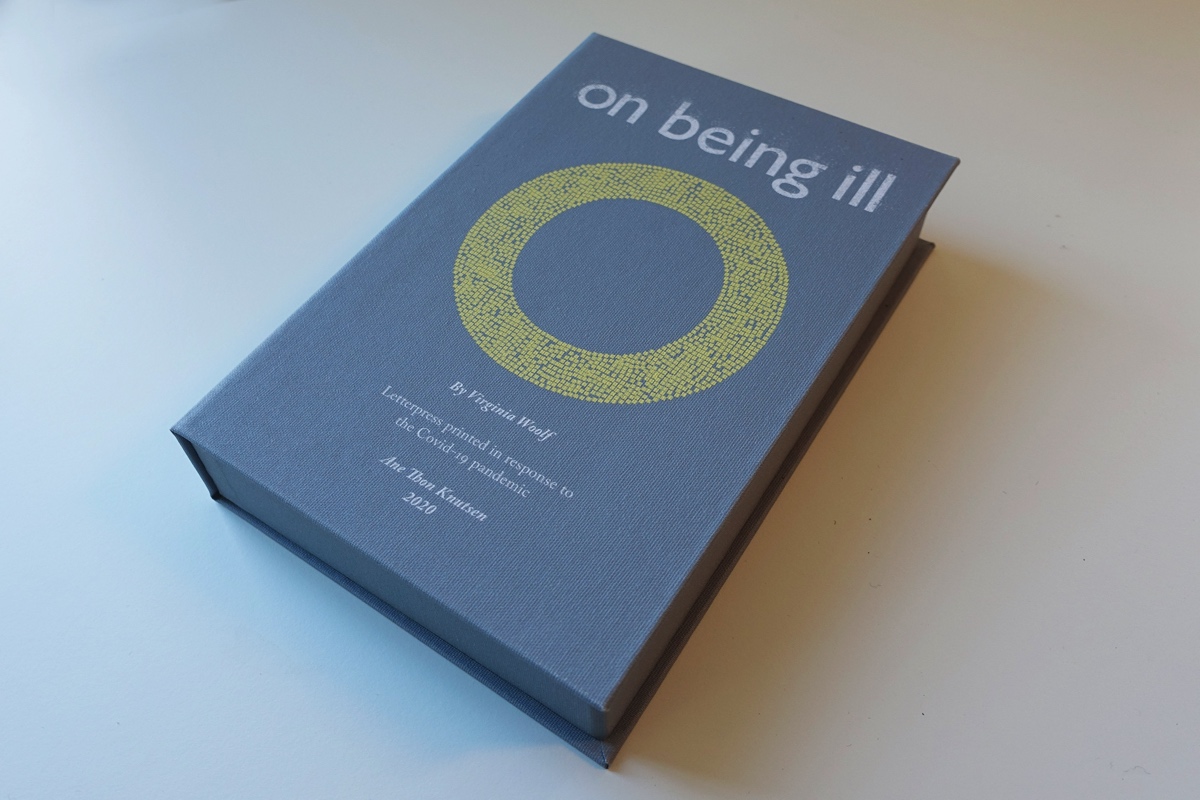

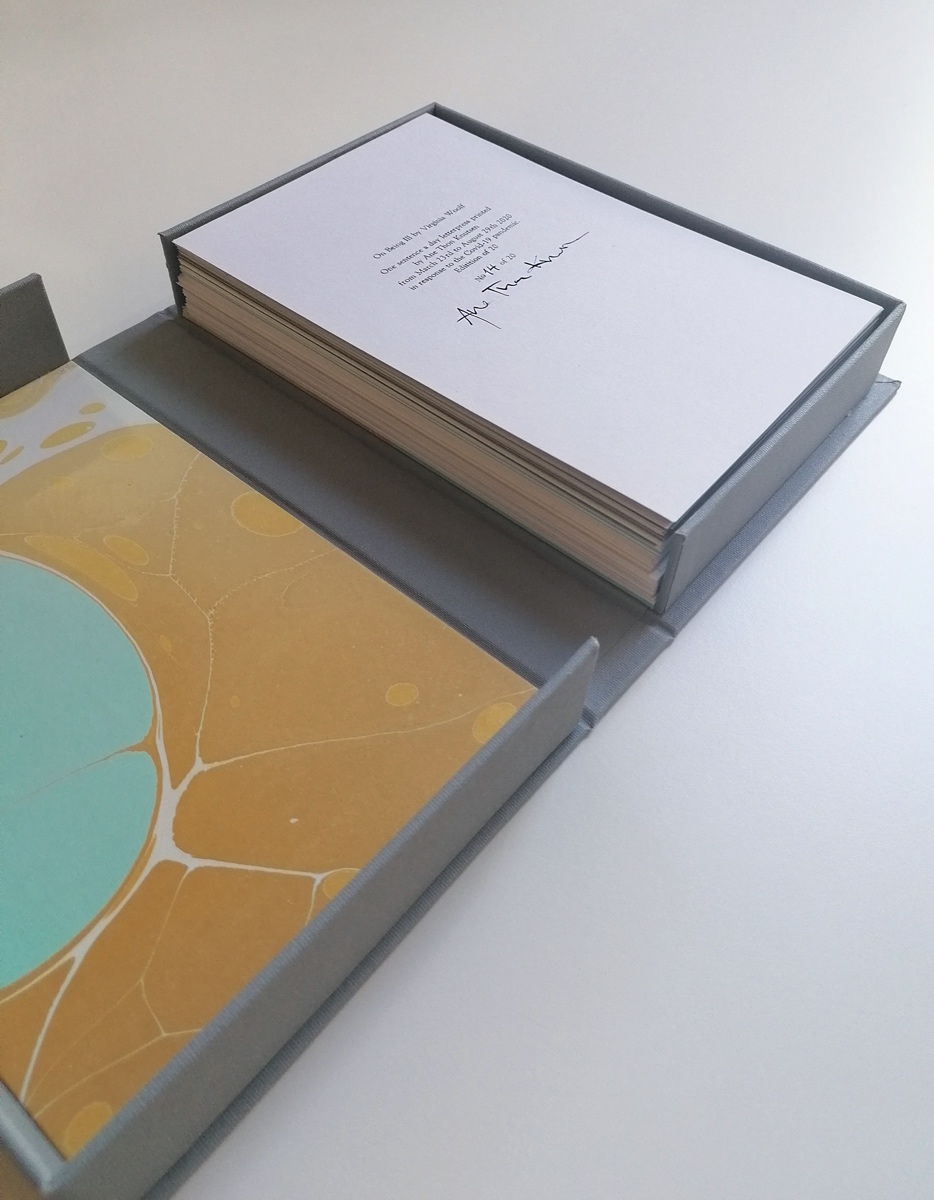

So, what could I do as I suddenly was isolated, but nonetheless wished to contribute to the outside world? I like working on my own, and I am lucky to have a workshop in my basement, but we also have a four-year-old at home. Therefore, I structured a quarantine-project that could work with the situation I found myself in: To typeset and print one sentence from the essay each day, on single sheets in an edition of 20, until things would get back to normal. The only paper available was what I had in the workshop, and...

“...i made it a rule to share each day’s printed sentence on Instagram and in that way invite to a collective slow reading. Along with the sentence of the day, I shared my own reflections about the sentences, my experience through the pandemic, effects on the work and the flow of time.“

Selected reflections:

Fourth sentence from On Being Ill by Virginia Woolf.

Last night I read a post by Paula Maggio on Blogging Woolf How Virginia Woolf survived a pandemic and lived to write about it. Many contemporary scholars reflects upon the fact that in history, the Spanish flu which killed 100m people, is far overshadowed by WW1, which killed 16m people. It reminds me of something I read in The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, by Ursula Le Guin; our history is told mainly through wars, the story of a hero and a villain, what Le Guin calls ´the murderer-story`. Is it so, as Le Guin writes, and Woolf too, that we need to write history anew, and even invent a new language for that? They are both discussing history of mankind through containers; how we have protected and carried things through the ages, from the womb to the coffin sort to say. And it makes me reflect upon what we are living through right now, where the majority of us are protected and contained in the safety of our houses. And it makes me wonder; how will this pandemic be portrayed down the line?

Tenth sentence from On Being Ill, by Virginia Woolf.

The story of the body's life, and the part the body has to play in our lives, is one of Virginia Woolf's great subjects. Far from being an ethereal, chill, disembodied writer, she is always transforming thoughts and feelings and ideas into bodily metaphors. She writes with acute - often extremely troubling - precision about how the body mediates and controls our life stories. – Hermoine Lee in The Guardian 18.12.2004

Fourteenth sentence from On Being Ill by Virginia Woolf.

Two weeks down. It feels like an instant and forever at the same time. I have no thoughts beyond easter. Until we have new guidelines from the government for the coming weeks, it feels like waiting for a bus in the cold. It’s this strange time perspective that I experience Woolf has captured so eloquently in this short story. Funny word even, short story. It certainly is not to me.

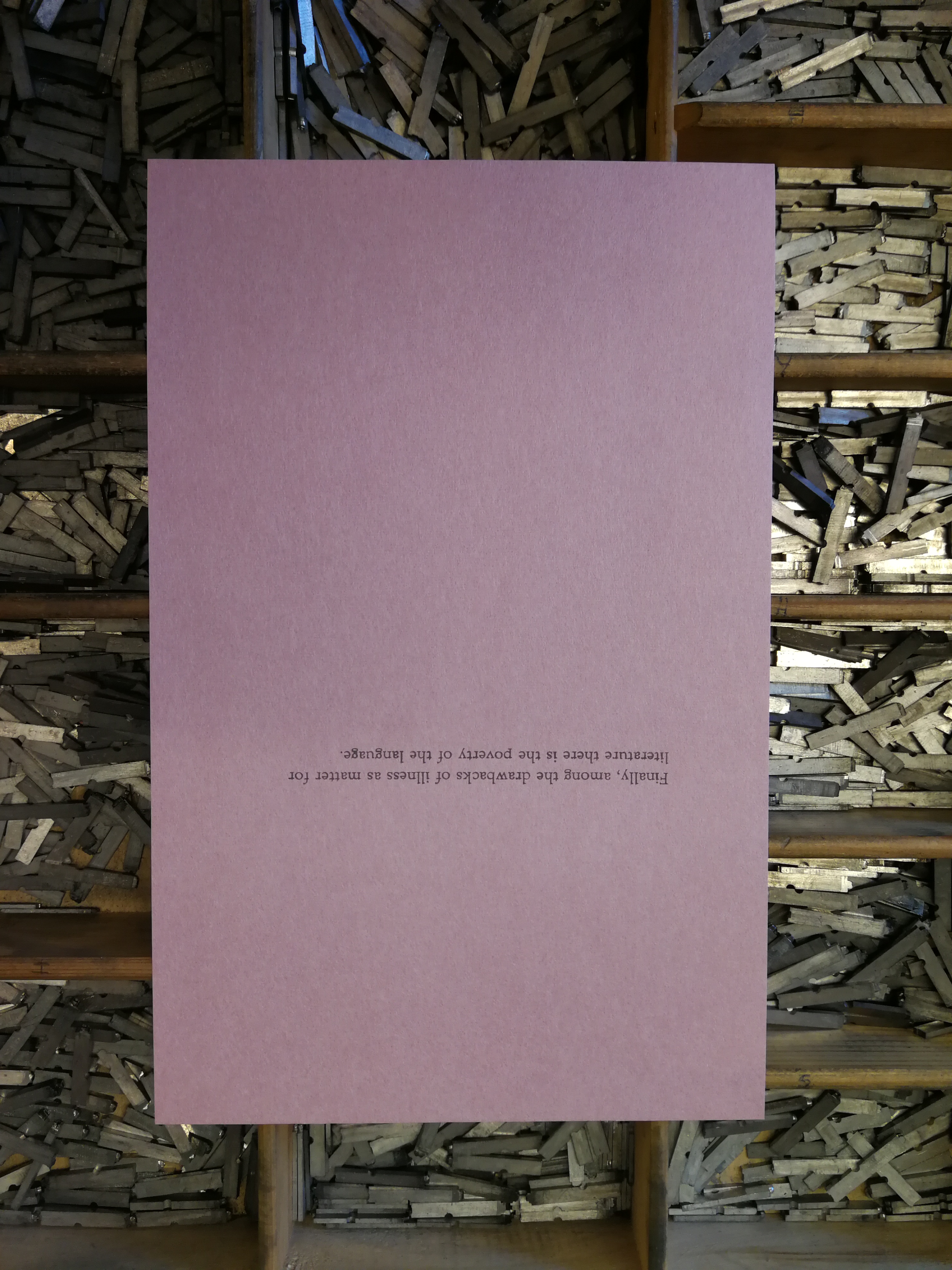

Fifteenth sentence from On Being Ill by Virginia Woolf.

As a practitioner, maker, designer, artist, whatever you call it, I very much relate to this problem with finding words. The words to describe what's happening when we are making, or are in the flow, or what I heard someone once call "the magic". In 1937 there was a series of lectures on BBC by the title >Words Fail Me. One of these was Craftsmanship by Virginia Woolf. It is a brilliant essay about the problem with words, their cunningness, shortcomings but also possibilities. This essay made me accept that words do fail, they will never express fully what we experience in our bodies and imagination, but sometimes they're the best we've got, and it is worthwhile trying to make them your allies.

Conclusion:

This project demanded more than five months of daily printing. I will not pretend it did’nt also feel like a burden, but mostly it felt calming to have this predictability to anchor me, to have a foreseeable narrative to guide me when in reality the future was unclear and uncertain.

“I used the narrative as a method to understand our own period in time, and that made me confident that this too would pass.“It also offered me a whole new perspective on 1920s art, as the project inspired me to read upon the context afforded by the Spanish Flu. Woolf’s text also gave me an idea for a course in narrative methodology with first year master students of graphic design and illustration, in which the students created adaptive works grounded in their own experience to do with Covid-19. The course, and my project, became a kind of therapy for the collective trauma we all were somehow affected by. I realised how universal the experience of illness Woolf expresses so brilliantly by turning a phenomenon that is wholly physical and separate from language into precisely that, language. And she turns it into a language that gives deep insight and recollection, and that leaves one feeling less alone in ones own ordeal.

This project demanded more than five months of daily printing. I will not pretend it did’nt also feel like a burden, but mostly it felt calming to have this predictability to anchor me, to have a foreseeable narrative to guide me when in reality the future was unclear and uncertain. I used the narrative as a method to understand our own period in time, and that made me confident that this too would pass. It also offered me a whole new perspective on 1920s art, as the project inspired me to read upon the context afforded by the Spanish Flu. Woolf’s text also gave me an idea for a course in narrative methodology with first year master students of graphic design and illustration, in which the students created adaptive works grounded in their own experience to do with Covid-19. The course, and my project, became a kind of therapy for the collective trauma we all were somehow affected by. I realised how universal the experience of illness Woolf expresses so brilliantly by turning a phenomenon that is wholly physical and separate from language into precisely that, language. And she turns it into a language that gives deep insight and recollection, and that leaves one feeling less alone in ones own ordeal.

The project is finished now, bound in boxes that hold loose sheets that are like pages ripped from a calendar. The publication is sold in the form of singles—each a sentence taken from the essay.

All the sentences are still to be found on my Instagram: @anethonknuts